Business as usual has failed – it’s time for a radical shift in drug policy

The latest figures on drug fatalities registered in England in Wales in 2023, released today by the Office for National Statistics, underscore the deepening crisis facing the UK.

Continuing a highly worrying trend, today’s numbers are the highest ever recorded. This is driven in part by the increased presence of nitazenes, a type of dangerous synthetic opioids just as potent as fentanyl, or even more so.

More worryingly, recent research by King’s College London shows that the ONS figures are likely underreporting the real number of opiod-related fatalities, due to the manner in which data is gathered and compiled. And while Scottish authorities have long introduced a system of quarterly reporting of drug-related deaths, figures for England and Wales lag behind by nearly two years, further obscuring the full extent of this real crisis. Partial data for 2024 and 2025 suggests that the numbers continue to rise.

Of course, not every drug-related death is preventable, but most are. Yet the problem is exacerbated by a long history of failed, punitive drug policies. Successive UK governments have consistently ignored incontrovertible evidence and refused to shift political attention and resources to the proven harm reduction interventions long shown to mitigate some the worst outcomes of problematic drug use.

The wide range of options includes drug checking services enabling the verification of substance contents at festivals and other venues, but also medically supervised drug consumption rooms (DCR) where people who use drugs find a safer environment to inject or otherwise consume their drug supply, with help readily available in case of an overdose. More than 100 such facilities operate in 18 countries now. They have demonstrably saved tens of thousands of lives.

The only such facility in the UK, The Thistle in Glasgow, has quickly proven its worth. In the first nine months since opening in January, it was accessed more than 4,700 times for injecting drug use, recording 60 medical emergencies. Not a single person died. However, it took campaigners several years of arduous work to clear countless political, legal, and bureaucratic hurdles to get to this point.

In the meantime, hundreds died, many because the fear of criminalisation pushed them into unsafe usage environments rather than seeking help. To date, no other drug consumption room exists. It is hard to understand why.

Aside from the real human costs of continued prohibition and criminalisation, it is also worth noting its economic impacts: data from Dame Carol Black’s independent review in 2021 estimates that £9.3 billion is spent every year across the criminal justice system in England alone on dealing with drug offences and drug-related crime.

In addition, roughly 10% of the prison population in England and Wales has been sentenced for drug offences, many of those non-violent, contributing massively to prison overcrowding. And yet, drug deaths continue to climb, and illicit drugs are more readily available than at any point before. The experience of many other countries shows that no amount of heavy-handed policing and tougher sentencing will change that.

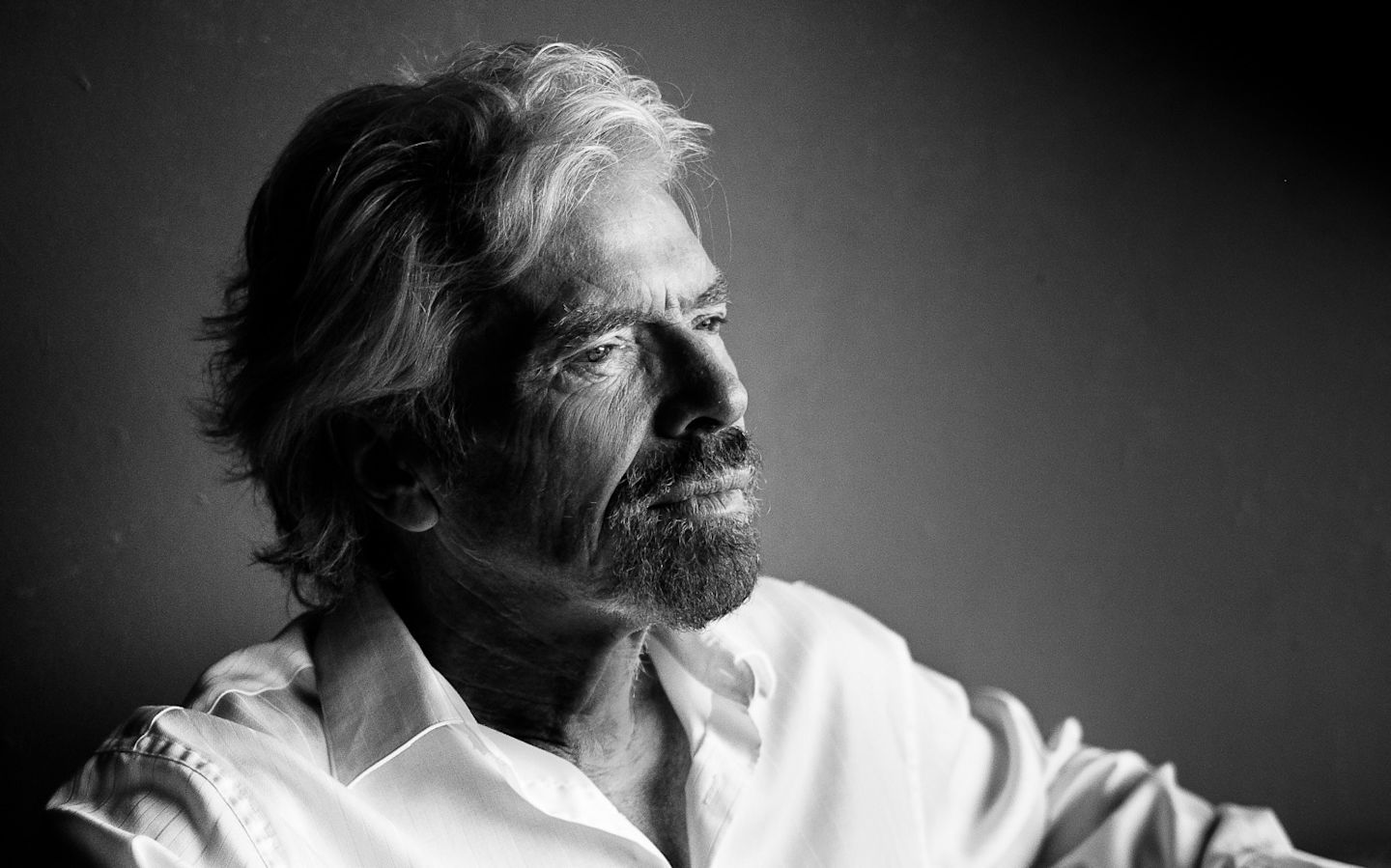

As a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, a collective of 27 global leaders committed to ending the failed war on drugs, it is painful to see the evasive contortions of many governments when it comes to engaging with the evidence and taking the steps we all know need to be taken. At the same, in places where sensible reforms were implemented the right way, with corresponding investments in treatment, housing, and prevention, such reforms have been popular, because they deliver results everybody wants to see.

As my fellow Commissioners and I have pointed out many times, decriminalisation of personal drug use and possession is an important first step to free precious resources and refocus law enforcement on what really matters. And investing at scale into harm reduction and other services is the only known way to reduce drug harms, bring down these shocking fatality rates and also reduce the economic costs of policing. Governments should also look into creating legal and regulated markets, as has been done with cannabis in many jurisdictions, limiting the size of the illicit market and creating revenue that can be spent on education, prevention, and treatment.

It is time for a radical shift in drug policy. Business as usual has failed.

When the opportunity to save lives is presented on a mountain of unambiguous evidence, nothing else should matter.

What better political legacy could one leave?